Is there a case for limiting director length of service?

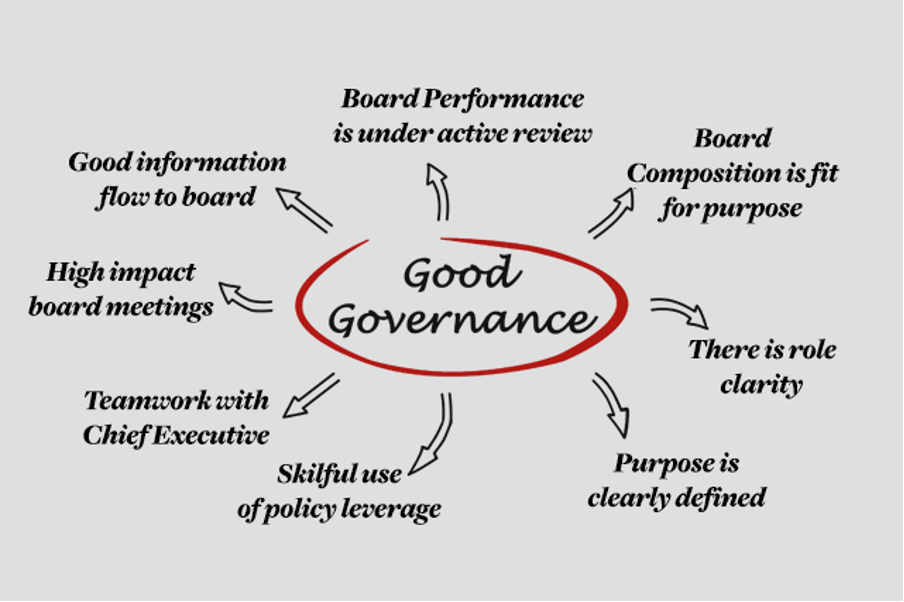

How long should your board members be on your board? And what's the best practice for tenure duration to ensure good governance is observed?

Mainfreight is one of New Zealand’s most successful listed companies. At its recent AGM, its Managing Director made a spirited defence of how long some of his board directors had been in office. His comments focused attention on a long-running debate about whether there should be limits to a board of director’s term length. This is not a concern confined solely to the commercial sector. Recently, the longevity of the board of the Laura Fergusson Trust was also in the news.

Internationally, there is an increasing trend for regulators to force boards to refresh their board membership by setting term limits for board directors. This intervention is often associated with a requirement for the number of ‘independent’ directors a board must have. It is common to associate a loss of independence with a long-term service beyond something in the vicinity of 10 years.

The Mainfreight case is interesting. It has been one of the best performing New Zealand publicly traded companies for a long time. Still, its four longest-serving directors have been on the board for an average of nearly 26 years. It is easy to see how institutional investors might start making a case for board term limits. Given the apparent struggles of the Laura Fergusson Trust, it is not surprising that its board, with its seven board members, who have served for a combined total of 96 years, has come in for adverse comment.

So, what are the pros and cons of setting a term structure for a director's length of service that supports good governance?

The case against limiting board tenure

Arguments made against setting board of director term limits typically include the following.

- Board member terms are a poor measure of director independence

- Forced board rotation can cause the premature loss of valued expertise and industry connections, and the loss of organisational memory to current decision-making

- A board with long-serving directors provides continuity – they are a bridge in the succession of the director, the chief executive and management

- Regular turnover can destabilise the dynamic of the board

- Forcing turnover in its membership makes more work for the board in the identification, recruitment, and orientation of new board members

- A new board member can take a long time to become fully integrated into the dynamics of the organisation and conversant with the capabilities of those on whom the business depends

- Replacing a long-serving board member weakens the board relative to management by diluting the board’s relative understanding of the organisation

- Board terms are inherently ageist and are therefore discriminatory

- Long-serving directors protect the culture of the organisation. Changing the board’s composition more regularly can destabilise both company and management

Learn how to manage your board with board management software

The case for limiting board tenure

There is also a wide range of strong arguments for setting board of director terms. Here are some examples.

- Every board needs a regular infusion of new capabilities, new ideas and fresh perspectives. Too little movement in membership risks institutionalisation and ossification

- Board term limits should stimulate an active succession planning process and help a board to fine-tune its composition to reflect the organisation’s changing operating environment

- Boards that lack new board member refreshment become increasingly vulnerable to groupthink

- The longer a director's term of service, the more entrenched they become and the more challenging to remove

- Entrenched board members stand in the way of an adjustment to increasing demands (and regulation) for greater diversity in an organisation

- Board members who serve for many years are likely to be increasingly comfortable with the status quo and committed to existing intra-board relationships

- Long-serving board members increasingly serve for the wrong reasons (e.g. for social status, continuing ‘relevance’, and maintaining valued social relationships)

- Longevity can overvalue past contributions at the expense of the future. Even if a long-serving director has been influential, their continued occupation of a board seat prevents a board member from joining who may have valuable skill sets to add to the organisation

- Board members may allow a colleague to hold onto a board seat for too long and be in breach of their fiduciary duty to act in the best interest of the organisation

- With a core of board members serving many-year terms, there is potential for a concentration of power that deters possible replacements and intimidates new members

- Provided term limits are staggered, there can be a better balance between continuity and member refreshment

- Unlimited term limits risks loss of director independence given, for example, the likelihood of an overly close relationship developing between long-serving directors, managers and board chairs

- A maximum year term requirement offers a respectful and efficient mechanism to exit passive, ineffective, or troublesome board members

Are there alternatives to a maximum length of service?

It is hard to argue that periodically refreshing a board structure and introducing a well-chosen new director or two is not a good idea. Vacancies need to be created to achieve this. If directors themselves do not know when it is time to go, what are the alternatives to strict term limits?

The most obvious is to have an effective individual performance review process. Most board appointments are for a specified term. Arguably a director’s term should not be extended without evaluating their current contribution and its relevance to the board's needs. However, robust independently facilitated individual director performance reviews are relatively rare. The usual excuse for not undertaking such a process - that it may upset relationships between board members - is likely a strong pointer to a board that needs change.

In the absence of director performance reviews, another option is to apply an active and transparent succession planning process. Done well, this is a continuing gap analysis comparing a board’s present capabilities with those it needs to grapple successfully with the challenges it faces.

Another option to trigger the appointment of new members would be to set a maximum average board terms. The result would not directly challenge the longest-serving board member when this maximum average tenure is exceeded. Other changes could be made to the board’s composition to bring the average tenure back below the limit.

Where to next?

- Explore webinars and masterclasses on governance best practice

-

If you're looking for a tool to streamline your Board processes, check out BoardPro by scheduling a demo today.

Share this

You May Also Like

These Related Stories

How to appoint a better board of governance

Introducing Simon Telfer - Another governance expert supporting the BoardPro community