Improving board effectiveness with an annual work plan

Written by: Graham Nahkies

Graeme Nahkies co-founded BoardWorks in 1997, Australasia first specialist governance consultancy. Since then the company has worked with over 600 client across all sectors Graeme came from a series of senior roles in local and central government. He is now BoardWorks Practice Leader ensuring BoardWorks stays at the forefront of contemporary practice.

Graeme Nahkies co-founded BoardWorks in 1997, Australasia first specialist governance consultancy. Since then the company has worked with over 600 client across all sectors Graeme came from a series of senior roles in local and central government. He is now BoardWorks Practice Leader ensuring BoardWorks stays at the forefront of contemporary practice.

Why does your board need an effective work plan? How does it become an essential tool in keeping your board’s attention where it counts? In this white paper we explore how increasing demands on boards are diluting rather than concentrating their focus, and thus reducing rather than improving their effectiveness. We examine just how little time most boards have to attend to even the ‘must does’, let alone the kind of thinking that will help the board to have a positive impact on organisational performance. And we show how a board work plan is an essential tool for identifying, agreeing, and delivering on the things that will give the board its greatest leverage over organisational performance.

Spoiler alert! We are not going to tell you what matters you should concentrate on. Only you know what those are, even if you haven’t got them figured it out yet. Were we to offer you a generic list of board tasks it might get you started, but your board’s capabilities and challenges are different from any other board. We will give you some signposts but the mere act of developing a board work plan produces 80% of its value.

We are going to start by telling you something you probably already know.

Table of Contents:

Pressure on boards is ramping up

How much time does a board have to fulfil its unique responsibilities?

Boards must apply greater awareness and intentionality to how they spend their time

Are we attending the right meeting?

Are we doing the right job?

Are we consistent and effective in prioritising the use of our time?

What are the benefits of a board work plan?

Constructing the board work plan

Conclusion

Free work plan template

The pressure on boards is ramping up

Change in the external operating environments facing modern organisations seems to be constantly accelerating. The world state once routinely described as VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous) is now referred to as BANI (brittle, anxious, non-linear, and incomprehensible)

Adding to their traditional preoccupations, boards are routinely bombarded with demands that even a decade ago would have been barely glimpsed let alone paid serious attention to organisational culture, money laundering, cyber risk, environmental sustainability, and social licence to operate, to name but a few.

Boards are also under pressure to engage with, and to balance and integrate the conflicting expectations of many different groups of stakeholders. Community values have changed and with those changes societal expectations of organisations and the products and services they produce.

On top of all that the pressures boards and their executive teams are under has been intensified by the internet. To make considered decisions boards have to filter out an overload of information, much of it no more than a noisy distraction. Almost anyone inside or outside of their organisation can publish their thoughts about it at a global scale. Any slip-up (real or imagined) that a board makes can damage or enhance its reputation and that of its members in an instant. If this was not challenging enough legislators and regulators are forcing boards and their members to accept greater accountability. This trend brings new and increased penalties, not just for bad behaviour, but for errors or omissions.

All of this means boards each have a ‘to-do’ list of seemingly infinite length. It is increasingly difficult for them to ‘keep their eye on the ball’, no matter how much time they put in. Interestingly, however, making the best use of board time is not a new challenge.

“Regrettably, most boards just drift with the tides. As a result, [directors] are often little more than high powered, well-intentioned people engaged in low-level activities. The board dispatches an agenda of potpourri tied tangentially at best to the organisation’s strategic priorities and central challenges.”.

Then, as now, most board performance evaluations surface complaints from their members’ that they don’t spend enough time on things that matter. It is puzzling why the complaint that boards are not addressing the real challenges facing their organisations in a sufficiently deep and thorough manner, is such an enduring one as boards really only have ‘Hobson’s choice’. The option of just accepting and reacting to whatever comes at them, responding only to the ‘squeakiest of wheels’, is hardly a choice for any board serious about its responsibilities. Ultimately, every board has to confront the reality that it can do something, but it can’t do everything. It is a matter of what a board will and will not allow to occupy its time and attention.

How much time does a board have to fulfil its unique responsibilities?

Just as individuals are (mostly) hopelessly over-optimistic about what they can achieve in a given time frame, so too are boards. Directors routinely report that their agendas are overloaded and that, consequently, many items are dealt with in ways that only skate over the surface.

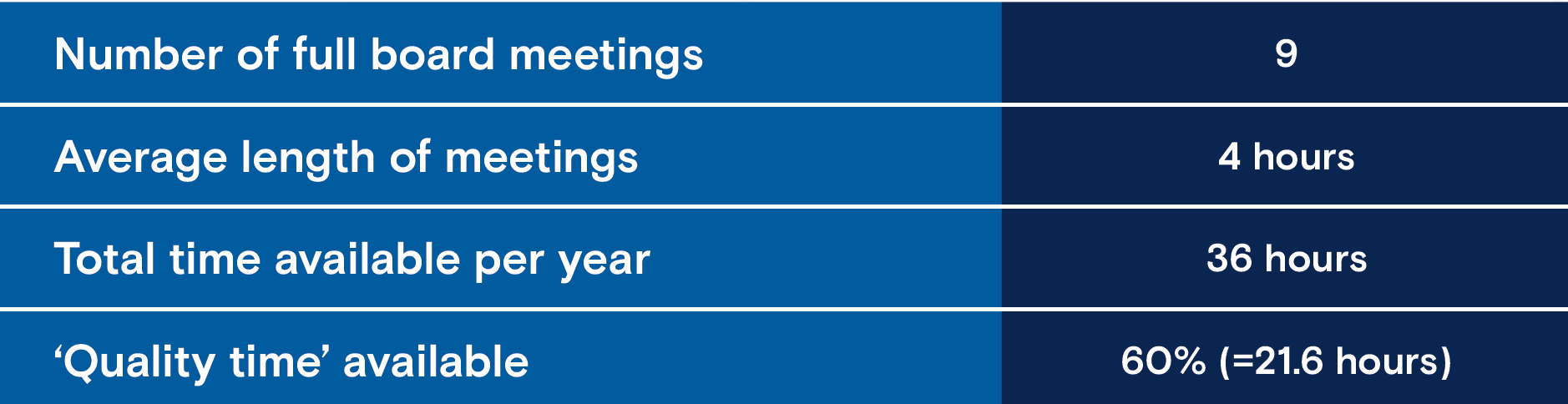

And yet few boards are particularly time sensitive beyond the start and finish times of their meetings. Even though time is arguably their most valuable resource, few boards start thinking about their potential work load from an awareness of the aggregate amount (in face time hours) they expect to have available over, for example, the next 12 months. Many will be surprised that it is likely no more (and possibly a lot less) than the length of time their senior executives would be on the job for in any single week.

They would surely be even more surprised if they discounted the actual ‘quality time’ available. There is a natural waxing and waning of individual and collective energy and concentration over the course of a board meeting. Realistically the board’s full attention is available for much less that the total duration of a board meeting. Let’s have a look at a hypothetical illustration to see what it might tell us about a ballpark figure.

In this example, even if the total time available is used optimally, less than 40 hours is available for vital board dialogue. After individual director inattention and time collectively wasted on matters to which the board cannot add value, the board is left with a very small residual to do its most important work. It is a wonder that any board is able to properly fulfill its constitutional accountability for organisational direction and control.

What boards have learned in responding to COVID imposed restrictions on traditional meeting practice is that in-person meetings are not the only way to carry out their functions. In future it is likely that many boards will adopt a combination of in-person and virtual meetings. It is possible, as we later acknowledge, that this might increase the frequency of meetings. But whether this will also increase the total time boards have available, is yet to be demonstrated. As they learned how to handle virtual meetings, most boards were also forced to recognise that video meetings need to be kept short if they are to be effective.

Whatever the future may hold, it is clear that a board’s effectiveness is highly dependent on its ability to invest whatever time it does have available, in conversations that matter.

Boards must apply greater awareness and intentionality to how they spend their time

This challenge is simple in concept but demanding in practice. It requires the board to first step back and examine how it is, and has been, spending its time. Armed with that analysis it can ask some key questions.

Are we attending the right meeting?

Too many boards let (even expect) their chief executives take the lead in determining what the board will work on. As a consequence, boards frequently end up attending to the matters their chief executives want them to, not to those that directors would themselves prioritise given the opportunity. Chief executives (and board secretaries) have an important role to play in advising on board meeting content and providing supporting materials. However, when the responsibility for deciding what the board will see and work on sits primarily with senior executives, the board is working for management not the other way around. To be fair, however, when executives compile board meeting agendas, they are often just filling the vacuum that results from board (particularly board chair) inaction. Whatever the reason, it means that directors are often at the wrong meeting. It is hardly surprising that so many corporate post-mortems conclude that the boards involved were ‘asleep at the wheel’.

Are we doing the right job?

This question points the way to a fundamental reflection on how the board thinks about its role and the value it brings to organisational wellbeing. For example, many boards have adopted the line that their role is primarily to monitor and ‘supervise’ management. That often translates into the comfortable and widely adopted mantra that ‘our most important job is to select the chief executive’. This has a convenient subtext which is ‘then get out of their way’. In contrast, some boards have a less hands-off definition of their most important contribution. For example, the members of many not-for-profit boards have agreed to function largely as amateur fundraisers.

Of course, chief executive selection and ensuring the adequate resourcing of business plans are core tasks for all boards. However, the dimensions of a governing board’s ultimate responsibility for organisational wellbeing are many and varied. At any stage some are more important than others and should be reflected in how a board allocates its attention.

Are we consistent and effective in prioritising the use of our time?

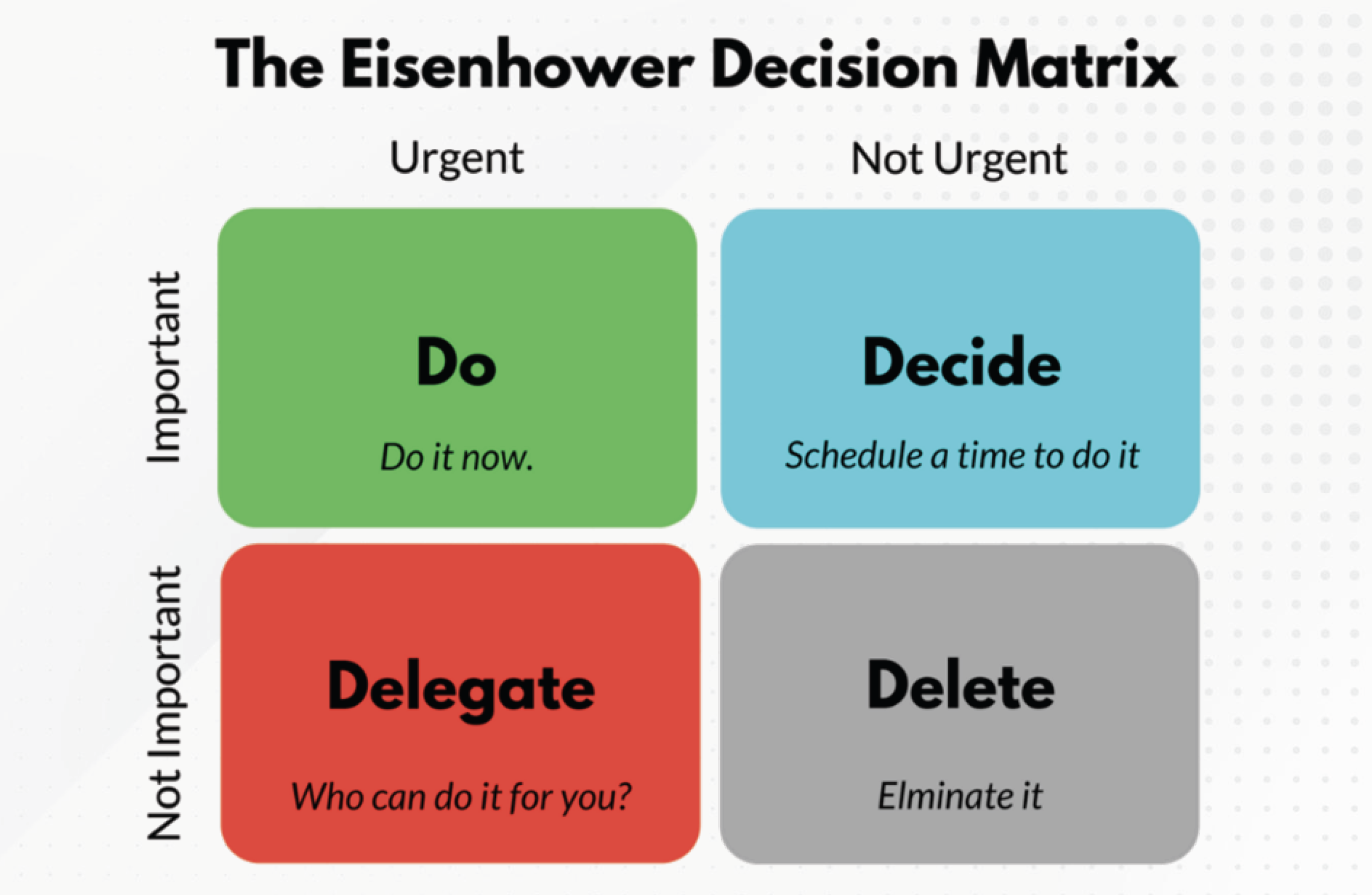

Firstly, the board needs to have some data on how it has been spending its time. To help with this analysis we have found it helpful to use a conceptual tool credited to former US President Dwight Eisenhower. Eisenhower came to public notice during World War II as a five-star general in the United States Army and the Allied Supreme Commander who prepared the strategy for an invasion of Europe. He subsequently served as the 34th President of the United States (1953 to 1961). In these roles Eisenhower was constantly faced with tough decisions about which of the many tasks facing him he should focus on each day. This led him to invent a simple two-by-two matrix. Widely known as Eisenhower Matrix it offers a method for prioritising according to two variables: relative urgency and importance.

Source: https://luxafor.com/the-eisenhower-matrix/

We recommend your board uses this matrix for a ‘quick and dirty’ time analysis exercise. Get board members to individually categorise the board’s use of board meeting time over the past few meetings. What percentage of meeting time do they think has been spent in each quadrant? Rough estimates will suffice. The main value of the exercise will be in consciousness raising and the subsequent debate about what meeting content was ‘important’ and what proportion of the board’s time was devoted to it.

After the matters considered important’ have been agreed, look at the pattern of their relative urgency. Inevitably some things will have been urgent as well as important. However, on closer inspection it is likely many topics in this category are likely a consequence of a lack of planning and preparation. This is a signal to the board to get busy with matters that are important but not (yet) urgent. Here’s a simple but common example. For want of a clear and actively applied director conflict of interest policy (important but not urgent) the board has to manage a crisis brought on by the ethical lapse of one of its members (important and urgent). Some boards seem to routinely find themselves in this kind of situation – dealing with crises they could have avoided, at the cost of spending more time on initiatives that would have prevented the crisis in the first place. Board’s that find more than, say, 10% of their time is spent in the important and urgent category could well be stuck in a classic version of a vicious cycle.

It goes without saying that boards, broadly speaking, would want to stay out of the kind of activity that can be allocated to the two ‘not important’ cells. The answer to avoiding this, as the diagram suggests, is to ‘delegate’ or ‘delete’. It is common for boards to find themselves dealing with matters that should never have come before them in the first place. Because distractions in the ‘unimportant and urgent’ category often relate to matters determined urgent by others’ that does not make them either urgent or important from the board’s perspective. To be fair, it is often not always possible for a board to determine whether something is important or not until it has had a chance to consider it. Those that don’t pass the test, however, should be dealt with as quickly as possible. This category will likely include matters that do not require close board attention, but which are there for form. For example, transactions that have been substantively delegated to management, but which need formal final board approval for legal reasons.

It follows, therefore, that the greater proportion of board time should be on matters in the Important/ Not Urgent category. Typical activities of that kind include:

- Strategic thinking (where are we now and what must we achieve?)

- policy making (setting expectations, creating a framework for delegation)

- Environment scanning (what’s going on out there that we need to take notice of?)

- Risk characterisation (what might prevent the achievement of desired outcomes?)

- Stakeholder relations (whose interests need to be factored into our decision making?)

What are the benefits of a board work plan?

The essence of a board work plan is not only that it is a list of important/not urgent topics that the board intends to deal with, but crucially that these are scheduled these into a meeting by meeting work plan. If the term ‘board work plan’ seems a little too prosaic it can also be referred to as an ‘extended’ or ‘annual’ agenda. This may be preferable in any case. Too many so-called board work plans are little more than a schedule of board and committee meetings, and other events that are likely to require board member involvement.

The annual agenda becomes the starting point for constructing every board meeting. Annual agenda topics should occupy the greater part of the meeting. They should also occur first in the order of matters to be dealt with and occupy as much as 60-70% of every board meeting.

By creating and applying an annual agenda, the board achieves many benefits. These include:

- Getting a shared sense of what the board should tackle and what is realistically possible in the time likely to be available. Is the board’s normal meeting pattern and the time that it usually commits up to handling that? What other options does it need to consider?

- Board alignment and collective ownership of the matters to which, over a period of time (say 12 months), it will devote the greater part of its time and attention.

- It helps spread the workload the board agrees to across the board meeting schedule ensuring as far as possible that there is not a peak load problem, and that agendas do not become over committed. Rarely will there not also be a need to accommodate important and urgent matters that were not anticipated.

- By the board committing itself (via the scheduling process) to deal with certain key issues (and thereby imposing a form of urgency) it reduces the temptation to procrastinate or be diverted by less important, less demanding matters that, because of their top-of-the-head proximity, could easily seem more pressing.

- Greater satisfaction for boards that they will be doing work that counts rather than just ‘drifting with the tides’.

- It provides a formal opportunity for senior management to advise what they feel should be on the schedule and when, without leaving them to take on the responsibility of having to direct the board’s work as well as their own.

- It will improve the sequencing of board deliberations so that each meeting constitutes a logical, iterative progression in the board’s thinking, and help ensure there is an appropriate build up to important decisions.

- It gives advance notice to board committees and management about the preparation required to ensure the board can properly consider the annual agenda topics.

- To the extent that management needs board attention to particular matters, these are well signalled, and the board can have confidence that it is being taken on a journey, that it will not suddenly be expected to rubber stamp management thinking that has been months and more in gestation.

- Ensures that the board’s work programme is realistic and that board meetings are not overloaded. A central objective of the board work planning process to spread the workload as evenly as possible across the board meeting schedule. Part of the preparation and scheduling process is, therefore, to estimate how much time it is likely to take to properly canvass and understand the issues and to reach a consensus on appropriate action.

- Ensuring there is enough time for important decisions and discussions is a counter to the tendency to rush through long, multi-item agendas only skimming over the surface of complex issues succumbing to the various cognitive biases that lead to suboptimal decisions.

- Greater clarity about what board and management, respectively, need to be working on, both separately and collectively, and to the extent necessary determines in advance the allocation of decision making rights.

Constructing the board work plan

Conceptually, a board work plan has two levels: the base load has to be the things that the board has to deal with whether it wants to or not. Let’s call this the ‘compliance’ layer. In practice there will be quite a lot of debate about what is on this list and about how much board attention (compared to board committee or management effort) is required.

Even though compliance (e.g., legal compliance) is important for the wellbeing of the entity, for the board itself this is the layer to which ‘delegate’ may be the most applicable action. Board attention is still required but can be focused on gaining assurance that compliance action has been taken and its objectives satisfied. Workforce health and safety is an example here. Chief Executive performance and remuneration review which is ultimately a contractual obligation is another. It is a compliance matter that cannot be delegated to staff, but the greater part of the work can be done by a board committee for recommendation to the board.

The second (upper) level consists of what we might call ‘discretionary’ topics. These will be mostly of the category ‘important but not urgent’. There are no prescribed consequences for failing to deal with these, but they are often at the root of organisational failure. Matters that are important but not urgent also have a habit of becoming urgent when not attended to in a timely way. This category contains the kind of topics that directors typically think about when they complain that their board is not being sufficiently ‘strategic’. Topics that will reach this list are unique to each board and relate to particular challenges their organisation faces and opportunities that may be open to it.

Frequently these will be matters about which there is considerable uncertainty. Also matters that, if a decision is required, have no right answer. The topics that go onto this second level list are likely to require extensive consideration and are often mentally demanding and stressful. Dealing with them may require considerable collective and individual courage. In short, they are the matters that demand the board to step up and justify its existence. It follows, therefore, that these are the matters which should take precedence and dominate board time and attention.

Compiling the compliance list is likely to require the combined capabilities of both board and key staff. External assistance may also be needed, for example, to gain a full sense of the organisation’s and the board’s legal obligations, and when these fall due. However, the next step must be board-led. Starting with a ‘blank sheet’ the board itself brainstorms what should be on the discretionary list. This is to get agreement on what are the most important things that the board has to get on top of over, say, the next 12 months. Don’t be surprised if between them board members come up with an initial list of 20-30 items or even more. And, before that list is closed off, ask the chief executive whether that board generated list includes matters that the executive team needs board decision or guidance on.

Then the board must collectively prioritise the list. Some boards have found a simple voting process works well. One technique is to give each member of the board a number of votes equivalent to the number of board meetings that would usually be held. The important thing is to force everyone around the board table to choose from the brainstormed list.

It is likely that a group of topics will emerge that has general support. The discussion then is about how much time the board will likely need to think through each and reach a consensus on appropriate action. As with the compliance topics valuable preliminary work to shape the issues for board discussion and deliberation can be done board committees or, better still, specifically convened task groups. Even then it is important that the board not be over optimistic about how many topics it can handle at any one meeting. Usually, one or two is realistic. Remember, most of these topics, by definition, have no right answer. Remember also that the whole purpose of the work planning process is to give the board a fighting chance to have the conversations that matter. Don’t be surprised if these kinds of discussion run on a bit!

One conclusion from this process might be that the board is not meeting often enough or for long enough to get through what it wishes to prioritise. However, the pandemic has forced boards to discover that there are other ways of getting board work done. One option that may become more routine is for boards to handle ‘business as usual’ (e.g., monitoring) in short snappy video meetings. Remember that the board’s monitoring function is simply to check that things are as they should be. This includes the compliance topics on the board work plan. This would help keep in-person meetings for the cognitively demanding topics that require more intense interpersonal engagement.

Conclusion

All things considered governing boards have no choice. No matter how many meetings they have or how long those meetings are, it will not be possible to do everything expected of them, let alone what they expect (or should expect) of themselves. Consequently, many, if not most boards, have to become more intentional about what gets their time and attention. It means better planning not only of what reaches their agenda but of when and how those things get dealt with.

In this never-ending endeavour, an extended or annual agenda (aka board work plan) is a great tool. In the end it is not about the quantity of time a board puts in but the effectiveness of the use to which it is put.

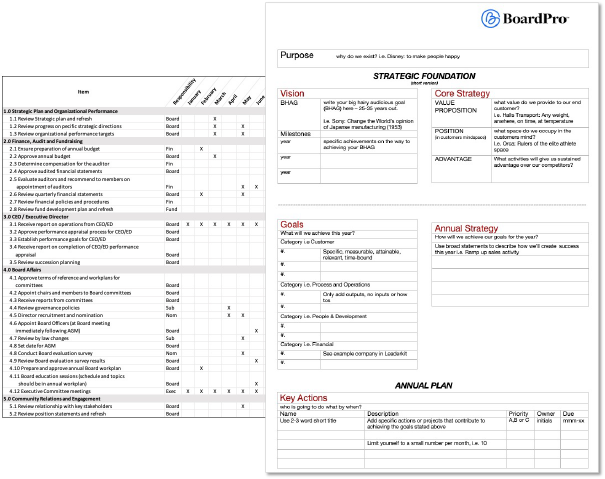

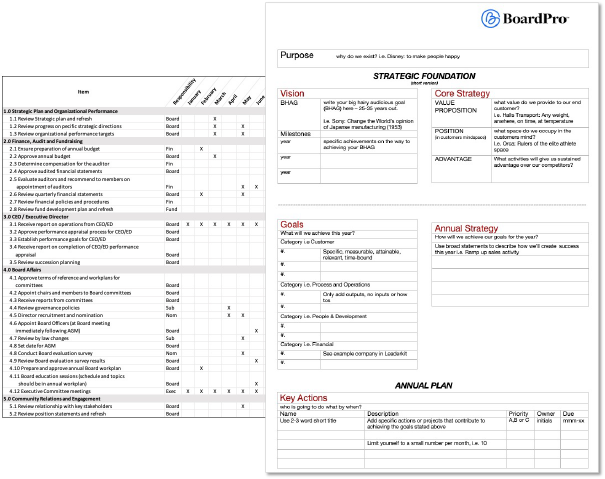

Free work plan template

Creating an annual work plan is often overlooked, especially for smaller organisations, as it isn’t seen as a key revenue raising or risk mitigating activity. However, it is imperative that your board creates a comprehensive work plan for each year. BoardPro’s Annual Work Plan templates and bonus Strategic Plan Template will help you and your board stay on track for the year ahead.

It can be hard to know what to include in your governance calendar, or how to set it out. With a no frills approach, our editable work plan templates are simple to fill out and maintain. Simply download the templates, add crucial dates, actions, and who will complete them. Having the following information on hand will make filling in your annual work plan much easier:

- Meeting dates

- Important dates, such as when company tax and statutory obligations are due

- Dates when key papers are due

- Actions you know need completing by the board or a board member/s

Once you’ve got your annual work plan you’ll be in good stead to create your one-page strategic plan. Although only a one-page document, there is some thinking and planning that must go into it. For example, your organisation's purpose statement: putting the purpose of your organisation into a few words is no easy task. Download the strategic plan templates now, and be prepared with the following information:

- Purpose

- Vision

- Annual strategy

- Core strategy

- Goals

- Key actions (from your annual work plan)

Get organised and download BoardPro’s annual work plan template and one-page strategy plan template now.

Interested in exploring paperless portal options for your company?

Schedule a demo with our team today and begin to experience a whole new way of meeting.

Share this

You May Also Like

These Related Stories

%20(1).png)

How to develop board guiding policies

.png)

How to write a board code of conduct